When it comes to helping farmers win the battle against weeds while reducing reliance on chemicals, you might say one South Australian company is crushing it. Kangaroo Island-based Seed Terminator produces a mechanical device of the same name which pulverises weed seeds at the harvesting stage, before they get the chance to grow up and run riot among crops.

The brainchild of the company’s co-founder, farmer/inventor Dr Nick Berry, the Seed Terminator tackles a problem inherent to crop farming: the fact the harvesting process is the weed’s best friend. Because when the crop is cut, once the chaff and grain have been separated, the harvester flings the chaff back onto the ground. This includes the seeds of weeds that have escaped or resisted the various stages of herbicide spraying – in other words, the toughest customers of all. When these survivors are redistributed, the whole harvesting process has simply set farmers up for problems the following year.

‘Problems’ may be an understatement. In 2016 Australia’s Grain Research Development Council estimated that weeds cost Australian grain growers about $3.3 billion annually, and – because weeds deprive crops of sunlight, water and important nutrients - yield losses of 2.76 million tonnes. They also put the cost of herbicide resistance at $187 million a year, for herbicide treatment and other weed control practices.

Nick’s invention is a smart and cost-effective solution. The Seed Terminator is an attachment that retro-fits to most combine harvester brands, and it uses multi-stage hammer mills to pulverize weed seeds along with the chaff so they can’t sprout. What's left is a fine sawdust-like mulch that actually puts nutrients into any soil that it’s spread upon. Installed on a typical harvester, the system can distribute that mulch up to 14 metres. It’s a one stop weed killer and mulcher as well as grain harvester.

So game-changing is this innovation, and its ever-evolving technology, that more and more manufacturers are entering the field. But the last thing Seed Terminator wants to do is smash its competition. Quite the opposite, because helping secure food production and rocking the status quo were always key to Nick’s vision.

“Our sole purpose is to stimulate change in world grain production, to tackle weed control that doesn't rely on chemicals alone,” says Nick. “We are not the only answer and we encourage others to innovate new ways to non-chemically control weeds.”

Let’s reel back a bit. Quite a bit, actually, to the 1960s. Back then, the herbicides available weren’t up to much, so farmers had to rely on tillage – churning up the soil prior to planting - to control weeds. They knew it wasn’t ideal.

“What tillage does, by its motion, is it rips the ground open and dries out the soil. If you are in a moisture limiting scenario like most of Australia, then that reduces your yield,” says Nick. Then along came a significant change. “All of a sudden we started to get some really effective chemicals come out, like glyphosate, which facilitated a whole change in agricultural practice. We moved away from tillage altogether, particularly in Australia.”

Still the world’s most used herbicide, glyphosate saw yields go up, and a lot of area that wasn’t suitable for cropping suddenly became viable. Then come the 90s things shifted again. “After 30 years, herbicides start to become an issue,” says Nick. Repeated use of the same herbicides led to herbicide resistance. A small minority of weeds of one particular species, thanks to a slight genetic variation, would be resistant to the herbicide. Over years of using the same herbicide, these survivor weeds would flourish and eventually dominate. The herbicides needed to be used more often and in stronger doses.

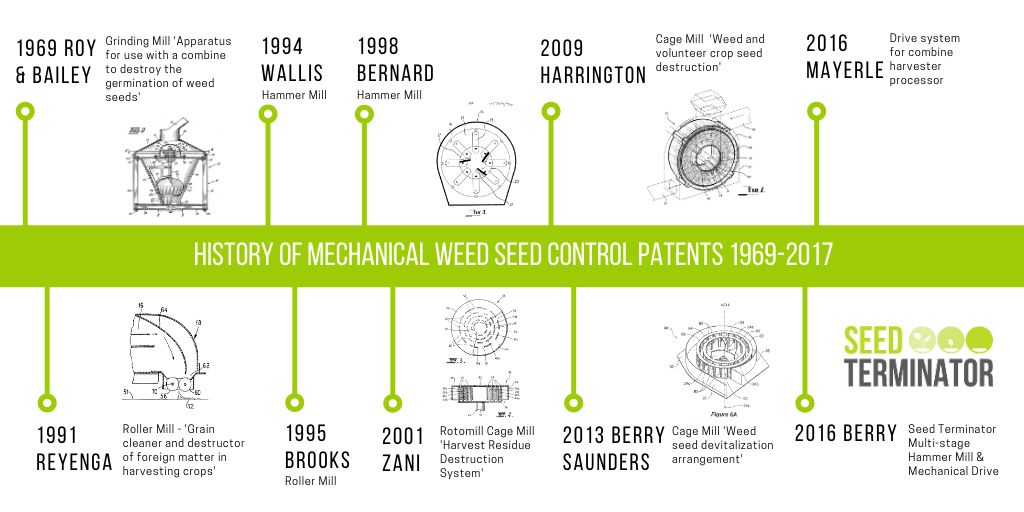

So the focus shifted back to the machinery itself, with a wholesale change in harvester design. Phil Zani of Harvestair had the Rotomill Cage Mill working by 2001 but between 1995 and 2005 there was a doubling in capacity of machines and the design couldn't handle the throughput. There was a lot of investment in making these mobile factories more efficient, but the central problem remained; combine harvesters weren’t killing the weeds, merely redistributing them.

Enter Nick. The farmer’s son and mechanical engineer had been paying close attention to developments in the field, and knew there must be a better solution.

From 2010, the GRDC had stepped in, with money. They began to fund the work of farmer Ray Harrington, who had the idea of attaching to a trailer a heavy-duty mill originally designed to turn coal into briquettes but which could also crush weed seeds. But the Harrington prototype came with a few problems. First, weighing in at one tonne, the mill was a colossus. Second, it had to be trailed behind the harvester (class 9 or larger mind you). And then the biggie: the price tag. It was going to cost some $250,000 – out of reach for most farmers.

“GRDC started to put money into it, and to realise that they needed some engineering.”says Nick The GRDC had engaged a consultant, Graeme Quick, to look at the prototype of the Harrington Seed Destructor (HSD). Quick concluded it would never be accepted by the American market unless it was integrated into the harvester. He proposed that a parallel project look into an ‘integrated weed seed terminator’ – (“The name Seed Terminator is my tribute to the great man,” says Nick).

The project was to be run at the University of South Australia (UniSA) and, largely funded by grain growers’ levies through the GRDC, Nick was granted a scholarship for the work. His PhD research was to explore ways to kill weed seeds on board a harvester. This started with a prototype – which failed. Then it was back to the drawing board, looking at how much energy was needed to kill weed seeds. Then creating some computer modelling process to evaluate how to evaluate energy input into seeds in a mill.

Five and a half years later, result: the IWSD (Integrated Weed Seed Destructor), mechanically killing weeds at harvest but which was now optimised for weed kill (not coal) and able to be retro-fitted into a harvester.

After leaving uni in 2015 to go farming on Kangaroo Island, Nick tried and failed to win the rights to commercialise the IWSD. “They wanted to sell it through just one brand of dealership at a $160,000 price tag that was out of reach, which I didn’t rate.”Link to Dr Nick Berry's PhD > Optimisation of an impact mill that processes chaff exiting a combine harvester to devitalise annual ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) seeds Nicholas Berry, BEng(Hons)

^ Dr Nick Berry back in 2012 with the original Integrated Weed Seed Destructor (renamed iHSD)

For Nick, this went against the grain. His research had been funded by all Australian farmers through their GRDC levy, after all, and yet the commercialisation plan presented to him was biased toward larger combines of one colour. He wanted the device to be suitable for most machines – and to be available to farmers big and small.

“We’ve got farmers who are anywhere from 600ha to 20,000ha and they all run different brand harvesters and different size ones, but they all have sustainability issues with herbicides. They need an integrated approach, to be using herbicides but to protect them from resistance, and drive down the weed population with something mechanical. Our vision is to reach as many farmers as possible, as quickly as possible and as economically as possible. Affordability is really important. While we develop the tech, we also need to reinvest in making it better.

And so Nick set about developing his own machine. The first pilot Seed Terminators were introduced in 2016, and now there are some 250 machines in operation worldwide, each retailing for around $110,000.

The design is constantly being refined but essentially it’s a mechanical system that uses the harvester’s drive to transfer power to two multi stage hammer mills. These grind, shear and pulverise the chaff once it has been been separated out from the grain – ensuring even the toughest weed seeds won’t be back.

“With chemicals you have ‘pre-emergent’ herbicides, that you put down at the time of sowing,” explains Kelly Ingram, marketing director of Seed Terminator. “Then you have in-season herbicide spraying while the crop is growing. We come in at the end. We tidy up all the weeds that have been missed. Potentially they are herbicide resistant, or perhaps they grown later and managed to dodge the herbicides.”

After working closely with farmer research partners over some 296 harvests, the Seed Terminator technology is paddock proven and farmer focused, says Nick. While they’ve increased the number of weed seeds killed by the mill, that’s not the only measure of achievement. They’ve also evolved the mill technology over the past four years to drive down the cost of the wearing parts and how long they last, and to increasingly decrease the amount of power used in the process.

Seed Terminator also conducts ongoing trials in a number of universities in both Australia and overseas to test the ability to kill weeds. The University of Adelaide testing found the device able to kill 99% of notoriously tough rye grass seeds. “Seeds come in different shapes and sizes so you need to apply different amounts of energy to kill them. How we set the mill up in different parts of the world varies slightly. We also do field trials on how many seeds we can capture with the harvester.”

Explains Kelly: “We have designed our technology so it can be pretty much used anywhere. The standard technology will go out to 98% of our farmers and will work fine and the other is the high capacity for when you have tricky conditions. The standard one works well in most situations."

While the Seed Terminator is getting uptake in Europe, Canada and the USA, it’s all still a learning curve, says Nick. “We’re just trying to understand how it fits into other people’s farming systems. One of the biggest learning things is mindset differences and attitudes. Farmers in Australia are very innovative and happy to modify their machines and do something a little different in order to give them a long-term benefit. We hear words repeated like ‘I want to be able to leave my farm in a better state than I found it’. It’s a generational thing – they want to hand down the farm to their kids and grandkids.”

He believes the public perception of farmers is often skewed, but Australian farmers’ ready adoption of technology that protects the land is tangible proof of how invested they are in longevity. “To go and spend $100,000 on a Seed Terminator is amazing.”

“Farmers care deeply about their land and its ability to produce food for the world. That long-term attitude isn’t only in Australia but it is pretty unique. People come here and are gobsmacked that a farmer would spend more money on something that’s not necessarily going to deliver him a return this year but over the next four years.”

Farmers are out there, day in day out, closely observing the life cycle of the plants and the soil. “They see the issue. They see it doesn’t make any sense to spread weeds with their harvester,” says Nick. “With Seed Terminator, they are getting revenge on their weeds."

Quick to adopt new technology, farmers recognise innovation as their friend, says Kelly. “Farmers always have their finger on the pulse about the latest developments. People are coming to us; it’s farmers talking to other farmers, it’s word of mouth,” she smiles. “People are really excited about it. And it’s nice that it’s ag tech – it’s not an app. It’s a mechanical solution.”

Meanwhile, Nick sees it as Seed Terminator’s mission to stimulate change, through commitment to R&D and developing further mechanical solutions to help farmers protect their crops. “We’re not only looking at how we can smash seeds but the whole system - how can we mechanically intervene to make farming more sustainable. We want to look at this as a holistic thing.”

And from here, who knows where this journey of innovation will lead, but thank you to all grain growers who played a part thus far.